Commentary: Here's why farm water use reports are exaggerated

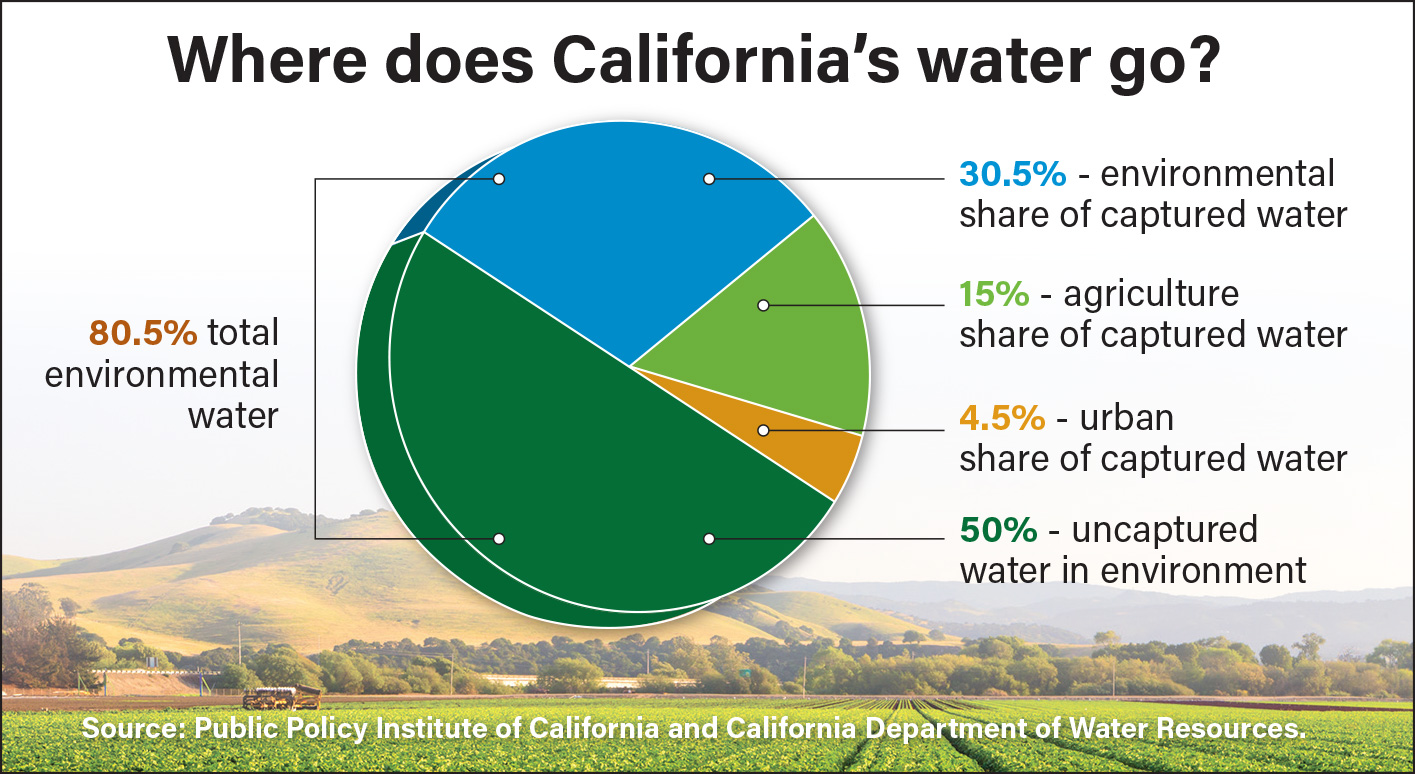

Farming in California produces the largest share of America’s food supply. And despite descriptions of agriculture as a major water user, the majority of California water stays in the environment.

By Amrith Gunasekara

You may have heard it repeatedly through local and national news outlets or from organizations critical of California’s agricultural water use.

At the height of a historic drought in 2015, for example, The Washington Post published a report titled “Agriculture is 80% of water use in California.” And a 2022 report by Food and Water Watch, titled “These industries are sucking up California’s water and worsening drought,” again noted that, “in California, 80% of our water goes toward agriculture.”

Really?

Before we explain just how much that 80% figure is taken out of context, this fact is worth noting: Water for farmers in California produces by far America’s largest food supply, including staples that are affordable, safe, nutritious and essential for our daily lives.

Now back to percentages. An internet search with the keywords “agriculture water use in California” provides information from universities and research organizations, which highlight that agriculture uses 40% to 50% of water in California. But those numbers are derived from the state’s “captured” water, which varies widely.

For example, 2006 was a wet year when the state received more than it could capture and hold, and 2014 was a dry year when it got a fraction of normal moisture. Wet and dry years are expected to get more unpredictable—and extreme—as climate change intensifies.

Regardless of wet or dry years, academia and leading water organizations recognize that agriculture uses about 30 million acre-feet of water to irrigate some 9 million acres of California food production, with groundwater used in combination with surface water.

Our farmers lead in adoption of low volume irrigation methods, such as drip, subsurface drip, and microirrigation systems on more than 50% of irrigated acres. While 30 million acre-feet may seem like a lot, we must consider the total amount of water the state gets in precipitation. That number is 200 million acre-feet.

Therefore, agriculture uses 12% of that water in a wet year and 29% in a dry year. The environment—streams and rivers—gets 26% in a wet year, more than double that of agriculture, and 21% in a dry year, 8% less than farming.

In a wet year with above-average precipitation, about half of the total water the state receives is captured in its reservoirs. With around 104 million acre-feet captured in a wet year, agriculture’s share is about 30%. In a dry year, that share could increase to 40% to 50%, an amount often referenced by academia and research organizations for agricultural use.

According to the 2013 California Water Plan, a large amount of uncaptured water is due to evaporation, evapotranspiration (evaporation from agricultural and nonagricultural native vegetation), groundwater subsurface outflows, natural and incidental runoff, and precipitation that is added to the soil. Realistically, this should be considered “environmental” water as well, since this water is being released into the environment.

This water includes high flows during storm events that are not captured in the state, as California experienced in January. It is unclear why this water is neither considered “environmental” in the water plan and state reports nor included in allocations for water distribution among agriculture, the environment and urban use.

Suppose uncaptured water were to be considered in the environmental portfolio. In that case, the environment receives 80% of all the state water, while agriculture receives 15%. The unprecedented allocation of water to the environment over food production highlights how California’s leadership designated basic food and economic security as a secondary priority.

Many other developed and developing nations have a strong focus on agriculture and water allocations because they know that locally produced food is more affordable. It is better for the environment because less transportation of food means less greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuel use. Local food production also means more local employment.

It is disappointing that California, the fifth-largest economy in the world, does not prioritize its agricultural food producers, ensuring that our farmers and ranchers have the water they need to sustain California’s population.

Our state and federal agencies can undoubtedly do a better job of capturing more water. Gov. Gavin Newsom’s executive order to expand the state’s capacity to capture storm runoff in wet years by facilitating groundwater recharge projects is a positive step. And California needs to build long-overdue water storage infrastructure approved by voters.

Meanwhile, the next time you read an article that says agriculture uses 80% of the water in California, remember how wildly out of context that figure is. Once more, agriculture gets 15% of average annual water that reaches California. And farmers are conserving water, producing even more with less while providing for all of us.

(Amrith Gunasekara, Ph.D., is director of science and research for the California Bountiful Foundation, an affiliate 501(c)(3) of the California Farm Bureau. He may be reached at agunasekara@cfbf.com.)