Colorado River crisis tests a proud region

Despite holding senior water rights to Colorado River, Imperial Valley faces an uncertain future.

By Caleb Hampton

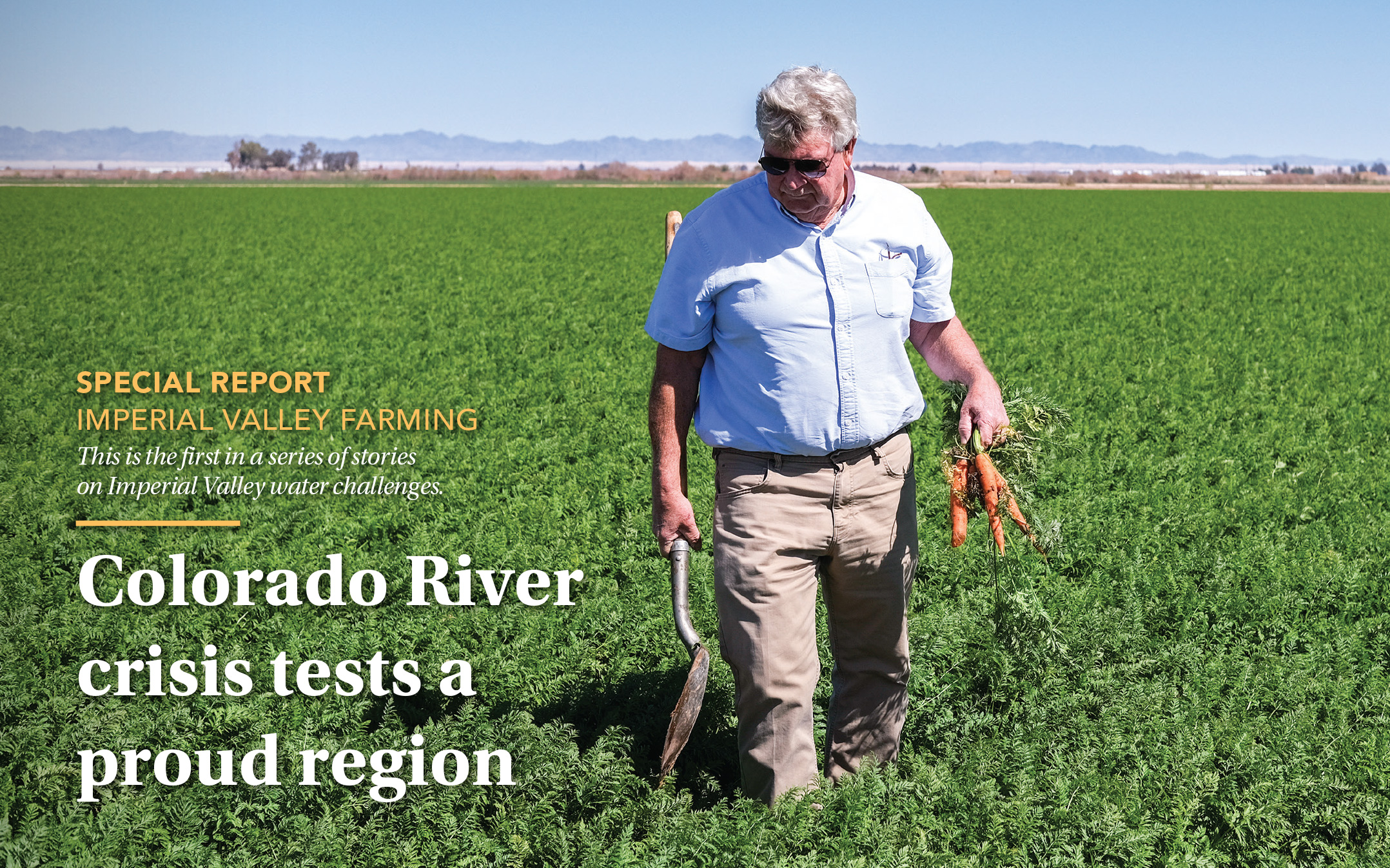

In late February, a dozen miles north of the Mexico border, farmer Mark Osterkamp walked across cracked earth and into a lush green field, plunging a shovel into the soil and pulling out a handful of cold, wet carrots.

Despite its arid climate, California’s Imperial Valley produces most of the U.S. winter vegetables, providing the lettuce, celery, cilantro, spinach, cabbage, broccoli, carrots and other crops that allow people from Seattle to Boston to eat salads and cook fresh produce year-round.

Unlike most agricultural regions, the Imperial Valley—with little rain and no groundwater—depends on a single source of water: the Colorado River. “That’s our lifeblood,” said Tina Shields, water manager for the Imperial Irrigation District.

Now, that lifeblood may be threatened, as competing interests battle over supplies from the depleted river and federal officials threaten to intervene. Despite holding senior water rights, which give them priority in times of scarcity, Osterkamp and other Imperial Valley growers face an uncertain future.

Fed by snowmelt in the Rocky Mountains, the Colorado River flows through seven U.S. states and Mexico, providing water to 40 million people in the West and irrigating more than 5 million acres of farmland, including roughly half a million in the Imperial Valley.

But the river is running dry. The basin states and Mexico have water rights to divert 16.5 million acre-feet from the Colorado River each year. For the past two decades, drought has reduced the river’s inflows to 12.3 million acre-feet. Key reservoirs, Lake Powell and Lake Mead, have fallen to record lows. Within two years, scientists estimate, Lake Mead could hit dead pool, no longer able to supply any water to the Lower Basin, which includes Nevada, Arizona, California and Mexico.

Last year, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation asked states to agree on a plan to reduce their use of Colorado River water by 2 million to 4 million acre-feet per year. In January, six states signed a proposal to cut the Lower Basin’s use by 2.9 million acre-feet, including 1 million acre-feet from California, about a quarter of the state’s entitlement.

California refused to go along, citing the “Law of the River,” a series of interstate water compacts, federal laws and court decisions that have governed water rights in the West for the past hundred years.

For centuries, the Imperial Valley was a barren desert. In 1901, land development companies diverted Colorado River water through a canal and into a natural overflow channel called the Alamo River, bringing water, agriculture and farmers to the Imperial Valley. It soon transformed from desert into abundant farmland.

Between 1910 and 1920, the county’s population grew faster than any in California. New landowners staked notices along the river where they diverted water and recorded their claims at a courthouse.

During those years, Walter Leimgruber, a Swiss dairy farmer, moved to the Imperial Valley and “homesteaded the land,” said Ronnie Leimgruber, an Imperial Valley farmer and grandson of the dairyman.

Under a government program, Walter Leimgruber earned the deed and water rights after working the land for five years. He would later rent out his 14 horses for the construction of the All-American Canal, which now transports water 80 miles from the river to the valley. “That’s how we got our water rights,” Ronnie Leimgruber said.

In 1922, the seven basin states signed the Colorado River Compact, establishing a system of senior water rights and junior water rights. “If you came and diverted water before that guy over there,” Osterkamp said, when there is a shortage, “you’re always going to get water before that guy.”

The system protected investments in the land and allowed newcomers to gauge future opportunities on remaining water availability. Many who arrived later acquired land with senior rights attached to it. Among them was Osterkamp’s grandfather, who emigrated from the Netherlands in the 1940s.

“It started on a shoestring,” Osterkamp said. “He bought a few acres. My dad expanded, and then I continued to expand, and now my son has continued.”

Today, the Imperial Valley has senior rights to 3.1 million acre-feet of the Colorado River, including 2.6 million in Present Perfected Rights, historic rights that predate the 1922 compact. When you are entitled to so much of the water, “you kind of have a target on your back,” said Shields, the IID water manager. “You become the easy solution to other people’s problems.”

For years, Imperial Valley farmers have looked over their shoulders as Los Angeles, San Diego, Phoenix and Las Vegas, uninhibited by the region’s limited water supply, grew exponentially. Their growth created water needs for millions of people. It also shifted the concentration of wealth and political influence.

“The water rights and water use of farmers in the Imperial Valley have been under attack for decades,” said Chris Scheuring, senior counsel for the California Farm Bureau.

The proposal this year from the other states, which sweeps aside California’s senior rights and applies drastic cuts across the Lower Basin, is the latest assault on the farmers’ water rights. “You have six other Colorado River Basin states pointing the finger at California,” Scheuring said. “And who they’re really pointing at is farmers.”

California countered the states’ proposal with an offer to cut its use by 400,000 acre-feet, roughly 9% of its allocation, including 250,000 acre-feet in cuts from the Imperial Valley.

“We live in the real world,” said Larry Cox, an Imperial Valley farmer whose family has farmed in the region since 1952. “Yes, we have this protection—the seniority—but they’re not going to be able to solve the issue on the river without additional water from Imperial Valley.”

Since 2003, the IID has transferred up to half a million acre-feet of water each year—about 18% of its allocation—to San Diego and other cities in exchange for water-conservation funding. It is the nation’s largest agriculture-to-urban water transfer. With the additional curtailments proposed by California, the district would be sacrificing almost a quarter of its allocation.

“That’s a really heavy lift,” Shields said. “We’re looking at what we might have to do to help solve the problem, but we’re also looking for the other basin states and water users to honor the existing agreements and the priority system.”

With the states at a stalemate over how to reduce water use, the federal government may step in and enforce cuts. Multiple Supreme Court decisions have affirmed the Imperial Valley’s water rights, but farmers are wary of “the court of public opinion,” Leimgruber said.

The assumption is, “People in Phoenix aren’t going to be forced to stop running their dishwashers so that farmers in Imperial Valley can keep growing alfalfa,” Scheuring said, referring to a water-intensive crop that has become a target for critics.

Beyond the Imperial Valley’s water transfers to San Diego and California’s new proposal, if any more water is cut from the valley, “we will grow less crops because we will be fallowing ground,” Leimgruber said.

Fallowing programs have occasionally been implemented in California to save water. But farmers taking land out of production is controversial due to the potentially devastating impacts on local economies. In the Imperial Valley, “we call it the F-word,” Shields said.

Imperial County, which is 85% Latino, is one of the poorest in the nation, with unemployment rates four times the state average. For those who do have jobs, one in six work directly in agriculture, with much of the remaining economy dependent on the sector.

“If you take away agriculture, we don’t have a community,” Shields said. “We don’t have a backup plan.”

The Inflation Reduction Act includes $4 billion in funding to address the Colorado River crisis, some of which could be used to compensate farmers for conserving water or fallowing their fields. It may also be used to support community funds to prop up local economies. But such outcomes remain speculative, and some Imperial Valley farmers view the prospect as a threat to their community and their way of life.

“More than likely, I’ll be made whole,” Leimgruber said, “but the effect on the economy will kill this valley.”

(Caleb Hampton is an assistant editor of Ag Alert. He may be contacted at champton@cfbf.com.)

Read the series:

Part 1

Colorado River crisis tests a proud region

Facing cuts, farmers step up on water conservation

Part 2

Desert farmers defend maligned alfalfa production

Part 3

As river runs dry, desert region is at a crossroads