Adding automation helps lower farm risk

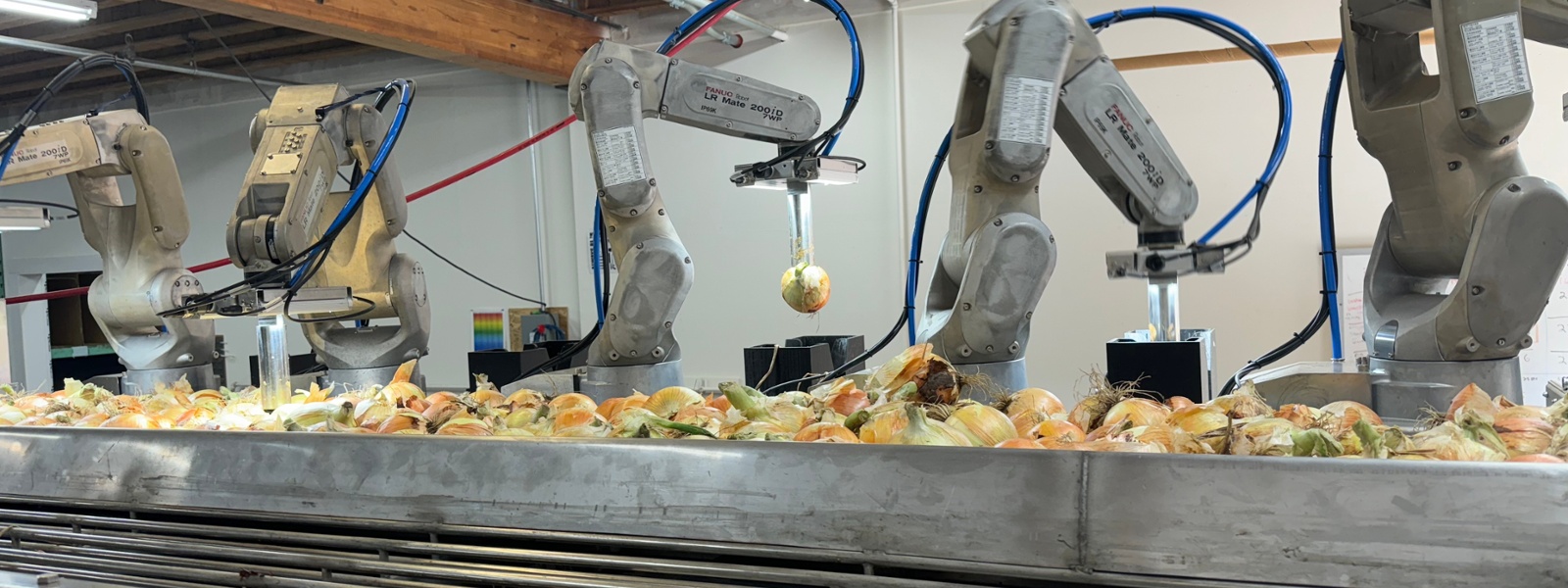

Robotic arms at Chiala Farms remove the tops, tails and peels of bulb onions prior to further processing.

Photo/Courtesy of Tim Chiala

By Christine Souza

Facing an inconsistent supply of employees, higher costs and growing pressure due to market instability, a grower-processor in Santa Clara County’s Silicon Valley has turned to technology to boost efficiency and stay competitive in the challenging produce industry.

Tim Chiala, chief operations officer of Morgan Hill-based George Chiala Farms Inc., has invested in more technology at his family-run farming and food-processing company.

“The supply of labor fluctuates like crazy, but hopefully by adding robotics, it will give us some stability,” Chiala said. “We can’t just raise the price to our customers every year or they’re going to go someplace else. This is a way to stabilize the price instead of having huge swings and then customers leave.”

George Chiala Farms grows garlic, peppers and spinach, and sources other produce that is processed and sold as ingredients to nationally known food companies to create salsas, soups, pizza toppings and more.

After a past crop failure of sourced onions from the Pacific Northwest, Chiala said he decided to add more automation for the processing side of the business.

“The price went up, and we already had a contract for the finished good we were making, so we got caught in this and lost money,” he said.

Three years ago, Chiala partnered with his childhood friend Justin Eckhardt, an engineer who worked at a robotics company for 25 years, to purchase the Auburn-based Saber Robotics and Vision Systems Inc. The two friends started an agriculture division and are testing prototype machines for processing vegetables.

The company creates robotics, vision systems and various automation projects for tech companies, startups and medical device companies, said CEO Eckhardt.

“We’ve always built automated solutions for different types of companies but have never really done a lot in the ag sector,” he said.

Chiala Farms is testing machines built by the company, including an automatic jalapeño de-stemmer and another with robotic arms that remove the tops, tails and peels of bulb onions. The latter has five robots and 10 cameras, and can identify onions as they’re coming down the shaker table. The machine then picks up the onions with suction cups and moves them to a set of knives, drops them into a peeler and out onto a conveyor.

“It is really cool to watch working because there’s basically five arms working in unison,” Eckhardt said.

The jalapeño de-stemmer uses artificial intelligence that analyzes visual data known as AI vision. AI cameras see images to detect stem location. Eckhardt said this information is fed to a set of knives that precisely cuts off the stem.

“It’s in no time at all, like 30 to 40 milliseconds, so it’s pretty fast,” he added.

Testing and perfecting the technology is ongoing, Eckhardt said, as he troubleshoots problems such as rocks and other foreign material from the field that interfere with the machines. The farm is working on different harvesting methods to make the equipment a little more viable, he added.

“We’re still trying to perfect these new methods,” Chiala said. “Ultimately, if we start making machines that are proven and functional, rather than a farmer or processor having to come up with $1 million for new equipment, we plan to lease the technology.”

To address labor shortages, reduce costs and improve efficiency, others in agriculture are looking for ways to add more mechanization. On the production side, work is ongoing to study the use of robotics and AI for tasks such as planting, harvesting, weeding, pest control, data analysis and transportation.

Robotics engineer and professor Stavros Vougioukas, vice chair of the Department of Biological and Agricultural Engineering at the University of California, Davis, said researchers and startups have developed robotic harvester prototypes for picking strawberries and apples.

“You have robotic harvesters that are trying to replace people, and you have harvest aids or technology that allows people to be more efficient and potentially safer when they harvest,” he said. “Most of what we harvest manually is not easy to mechanize because we are talking about crops where you need to harvest selectively.”

Machines created to harvest fragile crops, he said, must not destroy the crop but also pick in a selective and quick manner.

“These two metrics—efficiency and speed—are extremely important,” Vougioukas said. “This is where the struggle is—to build machines that are relatively cost effective and affordable that can pick quickly.”

Photo/Christine Souza

Engineers at UC Davis, he said, are working on robots that aid workers by transporting boxes or trays of picked fruit. After strawberries are picked, a worker would have to walk 200 feet to deliver the tray, walk back and continue picking, he said.

“All that time and distance is nonproductive; they spend anywhere from 15% to 30% of their time just walking,” Vougioukas said.

In addition, the lab at the university is working on a robot harvester prototype with multiple arms, the goal of which is to develop a machine with 20 to 40 arms that will be cheap, fast and effective.

Harvesting machines tested in the U.S. and around the globe are not yet good enough to pick 95% or 100% of the crop and pick it fast, Vougioukas said.

“What I see coming is some companies will be successfully deploying these robots to harvest a good percentage of the crop,” he said, “and then human workers will follow and pick the rest.”

Christine Souza is senior editor of Ag Alert. She may be contacted at csouza@cfbf.com.