Commentary: Balanced approach can best protect Colorado River

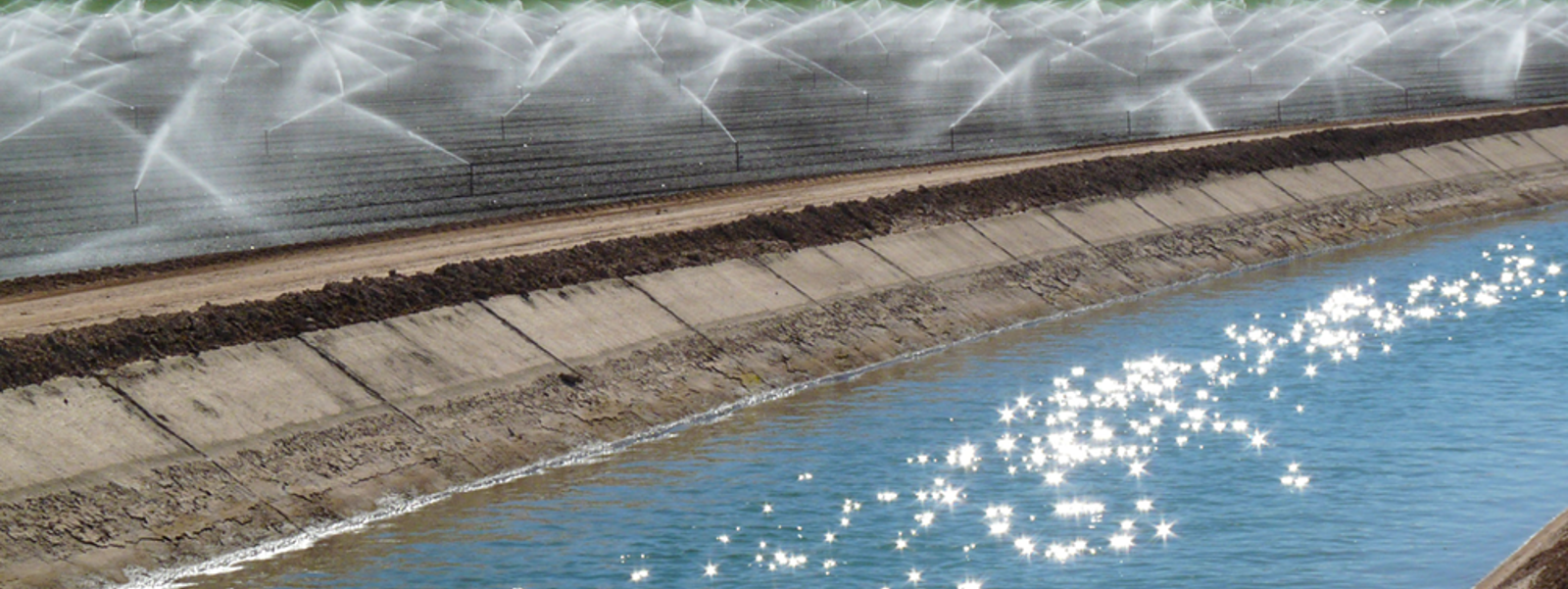

An irrigation canal carries Colorado River water to farms in the Imperial Valley, America’s leading winter vegetable region. Water conservation measures by farmers are helping to protect the river.

Photo/Courtesy of Imperial Irrigation District

By Mike Wade

As the lifeblood of the arid American Southwest, the Colorado River stands as a symbol of vitality and a testament to the intricate balance between human necessity and environmental stewardship.

Flowing through seven U.S. states and Mexico, its waters sustain more than 40 million people, vast agricultural lands that feed much of America, tribal interests and a myriad of ecosystems. Yet, despite its crucial role, the Colorado River faces an unprecedented challenge: Its robust flow has dwindled, signaling a looming crisis for population centers and millions of acres of critical farmland dependent on the river.

The Upper Colorado River Basin, consisting of Wyoming, Colorado, Utah and New Mexico, and the Lower Basin, comprised of California, Arizona and Nevada, have a combined interest in solving the crisis, and everyone that relies on the river must be part of the effort to ensure its long-term viability.

Since the passage of the 1922 Colorado River Compact, the river’s supplies have been equally divided between the Upper and Lower basins, each entitled to 7.5 million acre-feet, or 15 million acre-feet in total. However, a recent study by researchers at the University of California, Los Angeles, Center for Climate Science indicated that the Colorado River has lost 10.3% of its runoff since 1880.

Solving this requires a concerted effort to reduce demand on the river. And it must be done in a way that protects farm production, which benefits Americans on a national level and sustains local economies that depend on farms and farm-related businesses. The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, which oversees much of the river’s operation, is developing new guidelines to manage the river after 2026, when the current guidelines expire. The Upper and Lower basins submitted competing alternatives earlier this year, with distinctly different approaches to the problem.

The Upper Basin’s alternative centers on limiting releases from Lake Powell, which stretches from Southern Utah into Northern Arizona, to the Lower Basin. In other words, that means pinning the burden almost solely on the Lower Basin states should hydrological conditions worsen, while sparing Upper Basin states of additional water cuts.

In contrast, the Lower Basin’s alternative looks at managing the system as a whole, as it was designed by the bureau, which built seven dams and reservoirs—Mead, Havasu, Mohave, Powell, Navajo, Flaming Gorge and Blue Mesa—from 1931 to 1966.

For Imperial Valley farmers, the Colorado River is their sole source of water, meaning that any reductions in water supply without the benefit of conservation programs would have a devastating effect on the regional economy.

Still those farmers, who hold senior water rights to the Colorado River, have sacrificed, invested and innovated to save 7.75 million acre-feet of water during the last two decades. They have achieved water savings by largely switching to high-efficiency irrigation systems on thousands of acres of lettuce, broccoli, carrots, citrus and alfalfa.

Importantly, they have been aided in their efforts by a 2003 agreement between the Imperial Irrigation District, the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, the Coachella Valley Water District and the San Diego County Water Authority. The landmark pact facilitated agricultural water transfers to ensure reliable supplies for communities in exchange for financial support for on-farm conservation projects to help sustain America’s leading winter vegetable region.

California, Arizona and Nevada have also committed to reducing Lower Basin water usage by up to 1.5 million acre-feet per year, more than enough to offset the 1.3 million acre-feet of structural deficit, or water lost from the system due to leaks in canals and evaporation.

The Lower Basin plan is built on operating the system as a whole and allocates additional water supply cuts, when needed, evenly across both basins triggered by the reductions in the combined storage of all seven reservoirs. These types of solutions would be an effective way to address dwindling Colorado River supplies across the Upper and Lower basins, as California has done successfully between agricultural and urban water users for more than three decades.

The ramifications of a depleted Colorado River ripple far beyond its banks, impacting communities, economies and ecosystems that rely on its waters for survival. The Lower Basin Plan and 2003 agreement stand as examples of how parties can work together.

As California Colorado River Commissioner and IID board member JB Hamby said in support of the Lower Basin alternative, “Each basin, state and sector must contribute to solving the challenges ahead. No one who benefits from the river can opt out of saving it.”

That’s the kind of common sense the Colorado River needs. And our farmers are doing their part to protect this critical resource.

(Mike Wade is executive director of the California Farm Water Coalition. He may be contacted at mwade@farmwater.org.)