Climate-smart practices help dairies, nourish crops

Water conservation efforts are supported by U.S. Department of Agriculture grants awarded to dairy producers. DeJager Farms said the system benefits dairy and farming operations by reducing greenhouse emissions and curbing water use.

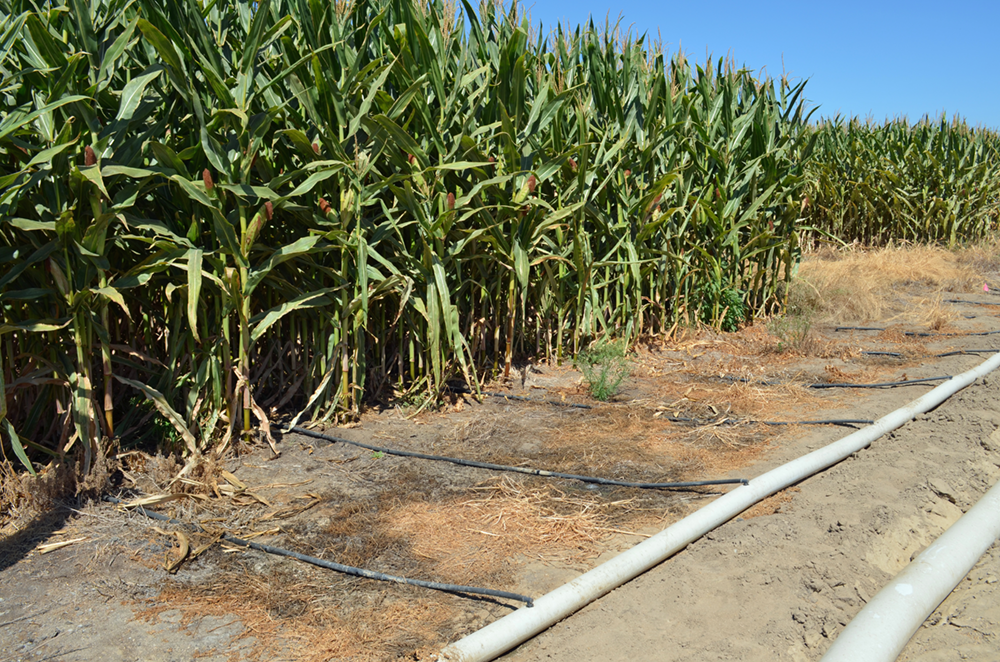

Photo/Vicky Boyd

Photo/DeJeger Farm

Photo/Vicky Boyd

By Vicky Boyd

Prompted by drought-induced water allocation cutbacks in 2014, the diversified DeJager Farms began looking at buried drip irrigation and manure water from its dairy operations to try to help its farming operations survive.

Since then, the Chowchilla-based producer of milk, beef, row crops and specialty crops has embraced the system. It has installed seven irrigation systems that treat and filter manure water from nearby dairy operations to support crop production. Two more systems are in the works for DeJager Farms, which produces forage feed for dairy cattle and crops such as processing tomatoes, wheat and almonds.

“The benefits we’ve found have just been enormous,” DeJager Farms Chief Financial Officer Richie Mayo said during a recent farm tour.

DeJager Farms was one of three operations in 2014 participating in pilot programs led by Sustainable Conservation, a nonprofit that promotes collaborative stewardship of natural resources, and Netafim USA. The nonprofit wanted to ensure that application of dairy effluent, as the nutrient-rich liquid is often called, saved water, protected groundwater and increased crop yields.

What was learned during the pilot has been applied to newer projects, which currently total 34 in the Central Valley, said John Cardoza, Sustainable Conservation senior project manager.

Many state and federal programs are now available to help underwrite the cost of such projects. In 2022, the California Dairy Research Foundation partnered with the California Department of Food and Agriculture and several dairy industry groups to secure an $85 million U.S. Department of Agriculture Partnerships for Climate-Smart Commodities grant.

Known as the Dairy Plus Program, it is designed to provide additional incentives during the next five years to dairy farmers who adopt advanced climate-smart manure management practices.

Under such efforts, not only has DeJager Farms experienced significant water savings compared to the farm’s former use of flood irrigation, but Mayo said the farm has also improved its water- and nutrient-use efficiency and uniformity while reducing overall nitrogen applications. At the same time, yields have improved.

The buried drip systems allowed the farm to get through the 2021-22 drought without fallowing fields even with 18% lower pump capacity than it had in the 2014 drought. Ten years ago, it had to fallow considerable acreage.

In addition, preliminary University of California research found that applying manure water through subsurface drip irrigation, also known as SDI, significantly reduces greenhouse gas emissions.

Over the years, DeJager Farms worked with Domonic Rossini and his team at Netafim USA to design and build the systems. All the components, including sand media filters, are standard to the Netafim product lineup except for the mixing valves.

Based on trial and error, Rossini said they’ve found what appears to be the sweet spot of drip tape with 14-inch emitter spacing and 0.16 gallon-per-hour output, installed in 40-inch rows and buried about 12 inches deep. DeJager Farms also has adopted 100% conservation tillage on its crops, except for processing tomatoes, allowing the drip tape to remain untouched below the soil surface for the roughly 12-year lifespan.

Manure from dairy barns first goes through a solids separator, where the larger material is removed. The resulting liquid then goes through preliminary treatment to further remove solids before it goes into a holding lagoon.

Producers don’t necessarily need a solids separator, but Mayo said the goal is to remove as much particulate matter as possible to reduce potential system clogging.

“The whole principle is to get the water as clean as we can and still hold the nutrients,” Mayo said.

DeJager pairs a manure-water lagoon with a fresh-water lagoon to allow blending or the option of using fresh water alone. An EC meter measures the manure water’s real-time EC, or electrical conductivity, which is a measure of salts and loosely correlates to nitrogen content. This can vary widely throughout the season depending on temperature, weather and the cows’ diet.

Based on the readings, a computerized controller blends the fresh and manure water to obtain the proper nitrogen concentration. Mayo can monitor the activities remotely from his smartphone as well as turn the system on and off. In addition, the system sends him alerts should something go wrong.

He bases his water and nitrogen applications on crop coefficients. Developed by the University of California, they factor in the crop, weather, planting date, growth stage and irrigation method to predict the plant’s optimum water and nitrogen needs at specific points in the season.

Mayo’s standard rotation is seven to eight years of alfalfa. After the stand is removed, he may move into processing tomatoes, silage corn and wheat for the remaining four to five years of the drip tape’s life.

For corn, he begins the season using fresh water to fill the soil profile before planting. As the plants begin to grow, he starts with a 15% manure-water concentration and slowly increases it to 40% when the corn is tasseling and has the highest nitrogen demand.

Because he is using SDI and making applications only when the plant needs it, Mayo said the farm has increased its water-use efficiency by 36% and its nitrogen-use efficiency by 45% compared to flood irrigation.

Depending on the variety, Mayo said, the farm harvests 32 to 33 tons per acre of corn silage using 220 total pounds of nitrogen per acre, with the nitrogn coming from the manure water.

When he used to flood irrigate, he would apply 300 to 380 pounds of nitrogen per acre and harvest about 26 tons of corn silage per acre.

In alfalfa, he said he has seen yields increase by about 40% and stand life nearly double.

An added benefit appears to be enhanced air quality. Preliminary research by a team led by UC Davis soil science professor William Horwath found using SDI to apply manure water significantly reduced emissions of nitrogen oxides, a greenhouse gas precursor.

(Vicky Boyd is a reporter in Modesto. She may be contacted at vlboyd@att.net.)