Fig growers work to expand the fruit's uses

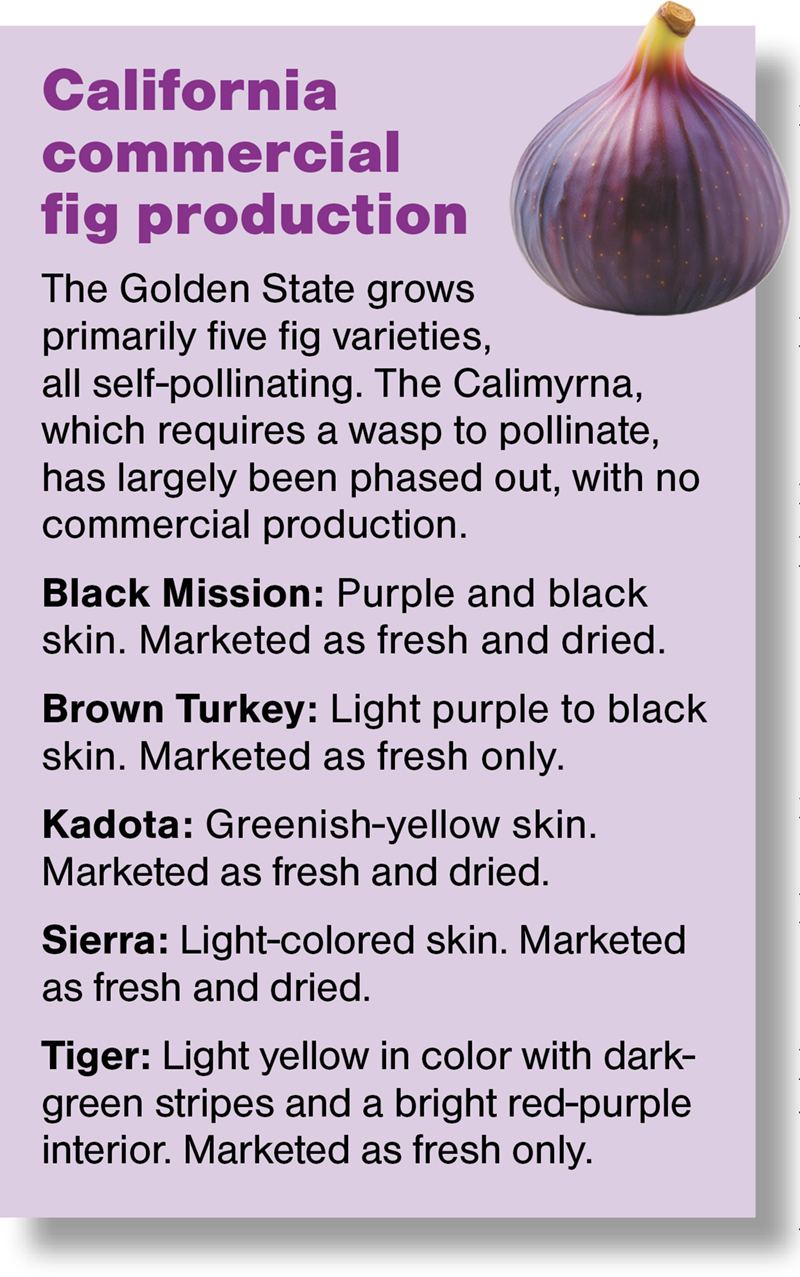

California fresh figs are packed for shipping at Catania Worldwide in Madera. While most of the state crop ends up as dried fruit, demand for fresh figs has increased. The San Joaquin Valley remains the top fig-growing region, with Madera, Merced and Fresno counties leading in production.

Photo/Christian Parley

By Ching Lee

Figs are in peak season, and California growers say they have a quality crop this year that more retailers should promote for fresh eating, even if most of their production still ends up going to make dried fruit.

They’ve been trying to change that for years by promoting fresh figs while they’re in season and educating consumers, many of whom have never tasted a fresh fig and know the fruit only as a filling for a certain type of cookie.

“We’re really trying to liberate the fig from the Newton,” said Karla Stockli, CEO of the California Fresh Fig Growers Association and the California Fig Advisory Board. “I can’t tell you how many times I still say that because a fig is more than a Fig Newton.”

There has been progress, she said, noting the “leaps and bounds” the industry has made in the past decade, thanks in part to innovations in packing the delicate fruit. The “foodies” movement has also helped raise the profile of figs as more chefs and adventurous cooks incorporate the fresh and dried fruit in their culinary creations. Demand for figs is up, Stockli said, with more people buying figs when they see them.

Whereas fresh figs used to be “more of an ethnic kind of product” popular with certain cultures, particularly those in Mediterranean countries, they have become more common in American stores rather than as just a novelty, said Madera County grower Steve Schafer. With TV cooking programs preparing figs to showcase the fruit’s color, texture and flavor, figs are now “very accepted,” he added.

“It fits very well into this movement where everybody is cooking and making food a very important part of their life, and figs are great for that,” Schafer said.

Schafer considers himself a relative “newbie” to the fig business, having planted his trees about 10 to 12 years ago. He grows strictly for the fresh market and prunes his trees much lower to the ground than other commercial orchards so that pickers don’t need to use ladders. This type of setup means he can’t mechanically sweep any dried figs that drop at the end of the season.

Figs dry naturally on the tree and then fall off. Farms that participate in the dried-fruit market typically stop irrigating sometime in September to facilitate drying. Schafer continues to irrigate to keep the trees green, so he can pick fresh fruit until the end of October. By pruning his trees more severely, Schafer’s harvest also starts later—in mid-July—when other farms usually begin picking their first crop in June.

Growers agree that timing of this year’s crop is more normal compared to last year, when late-season rains delayed harvest and affected fruit quality. This year, weeks of triple-digit temperatures in July made harvest more challenging, Schafer said, with more fruit ripening at once, narrowing the harvest schedule, which led to more culled fruit. This could affect overall volumes, he said.

California farmers remain the nation’s top producer of fresh and dried figs. But state acreage has fallen through the years, hitting a low of about 6,000 in 2022, when farmers were forced to remove trees due to drought, Stockli said. They also lost export market share on dried figs during the pandemic because of shipping disruptions.

“There were more imports that took shelf space, and we could not compete with that,” Stockli said, noting Middle Eastern countries, especially Turkey—the world’s leading fig producer—displaced California dried figs and fig ingredients.

But more trees are being planted to meet growing demand, she said, and other trees are coming into production. She estimated last year’s bearing acreage at 8,500. Current acreage is more in line with where the industry was in 2008, when acreage stood at 8,394.

Still, it’s a far cry from 26 years ago, when state plantings topped more than 16,000 acres. Erik Herman, whose family grows figs in Madera, Merced and Fresno counties, said he remembers the industry being much bigger in his childhood years, when there “used to be groves of fig trees” in Fresno. Now those orchards are houses and other developments.

Despite the shrinkage, Herman said the supply of California figs going to the fresh market has grown. To meet demand, his farm has planted more trees in recent years, with plans to plant more in the next three to four years.

With about 3,800 acres, his family remains the state’s largest fig grower. His father, Kevin Herman, started growing the fruit nearly 40 years ago, before the younger Herman was born. The farm produces figs for the fresh and dried markets. It harvests fresh figs from mid-July until about Thanksgiving, while dried figs are harvested from late July or early August until October.

“Popularity and different uses of figs have continued to grow over time, and I think it’s moving our industry in the right direction,” Herman said.

Whereas fresh figs used to be available mostly in specialty grocers, more traditional retailers carry them now, he pointed out. Stockli said the association has been working to get more retailers on board. Costco, Trader Joe’s, Whole Foods and Raley’s typically have them during the season, she noted, though she acknowledged other traditional retailers still don’t. Price point may be a reason, she said.

In the fall, when Mexico begins shipping fresh figs, California growers face some competition, Stockli said. Shipments to Canada, the largest export market for California figs, help relieve some of the domestic pressure. But during peak season from August into September, “we really are the only figs in town,” she said.

For the dried fruit, the industry has been working with product developers, niche manufacturing companies and food technologists, providing them with fig ingredients that could serve as a sweetener or to replace food coloring, so they could make a more nutritious product, Stockli said. Dried figs are now found in sauces, meal kits and confection, especially in baked goods.

Four California companies make dried figs: San Joaquin Figs, Fig Garden Packing and Valley Fig Growers—all in Fresno—and National Raisin Co. in Fowler. They produced some 7,400 tons of dried figs last year, an increase of 2,000 tons from the prior year. Dried figs accounted for 75% of state production in 2023, with 25% going to the fresh market. That’s compared to 80% to 90% of the crop used for drying more than 10 years ago.

Most of the dried fruit is made into paste and other manufacturing ingredients. But very little of it is used in Newtons, now owned by Mondelez International, which makes the cookies in Mexico and sources most of its fig paste elsewhere. California dried figs are finding their way into similar and new products though. For example, the blueberries in Quaker Oats’ instant oatmeal at one time were made with extruded fig pieces infused with natural blueberry flavoring, Stockli noted.

Merced County grower Marc Marchini said he wishes the market for fig paste were bigger but noted it faces competition from paste made from prunes, dates, cranberries and other dried fruits. His family is planting more figs, with a focus on the fresh market because of better returns compared to dried figs. He acknowledged the risk the farm is taking by the expansion, as figs are such a niche crop. But with the price of almonds and walnuts down, “there’s just not a lot of other options, honestly,” he said.

Even though the market can be tough during peak season when fig supplies are plentiful, he said he sees opportunities to sell more figs during the first couple weeks and the last four weeks of the season.

“Hopefully, we can expand some of these markets and have the retailers back it up with some sort of promotion,” Marchini said. “If it doesn’t work and we have too many (trees), I guess we take them out and we plant something else at that point.”

(Ching Lee is an assistant editor of Ag Alert. She may be contacted at clee@cfbf.com.)